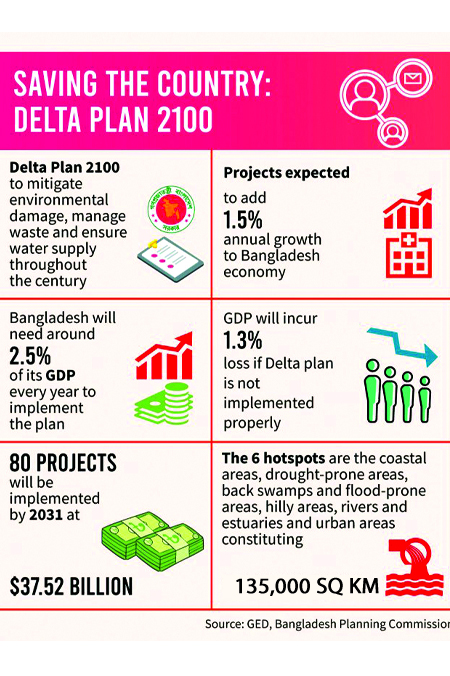

Once the maritime boundary disputes were settled with Myanmar and India in 2012 and 2014 respectively, Bangladesh gained ownership of more marine space, bringing the total marine space up to 80% of the country’s entire terrestrial area. The government has identified this area as a key source of economic growth for the country and to develop this space appropriately, the government has adopted the Blue Economy concept. This concept provides a framework according to which all ocean related activities may be carried out while still remaining environmentally sustainable.

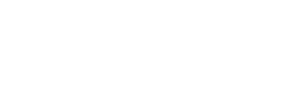

The Government’s Eighth Five Year plan focuses strongly on the Blue Economy concept as a means for greater economic growth. The concept also featured in the more recent Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100. In 2017, a new department under the name “Blue Economy Cell” was launched, and its main task was to increase cooperation between different ministries so that a definite path for sustainable development of the ocean could be forged. It also had the secondary task of answering important questions regarding the implementation of the five-year development plan.

The Blue Economy concept has become popular in recent years among the governments of coastal countries and islands. Nevertheless, it has still not been possible to finalise a proper definition of what the Blue Economy concept entails and how it can be applied. Once the Bangladesh government decided to implement this concept, they ran into a number of questions. Firstly, what would be a better way to measure the current economic uses of the ocean? Secondly, clearly identifiable targets need to be set for the sustainable use of this ocean space. And thirdly, a policy pathway needs to be set for getting there. The European Union (EU) and the World Bank collaborated to come up with a two-year technical assistance programme which is meant to help the government answer these questions. A study (Toward a Blue Economy: A Pathway for Sustainable Growth in Bangladesh) was conducted under that programme to create the primary measures of ocean based economic activity in the country. These measures were by no means able to provide a complete picture of economic activities, but they were an important starting point. The exercises which assessed these measures also led to identifying some gaps in the information and suggested some ways in which the government could fill those gaps. Examples of this include providing an estimate of the costs of environmental degradation caused to the oceans and the size of economic costs and benefits of development pathways. Since the government has decided to implement the Blue Economy concept, this study provided the government with some baselines according to which policy and development pathways can be evaluated and economic growth measured.

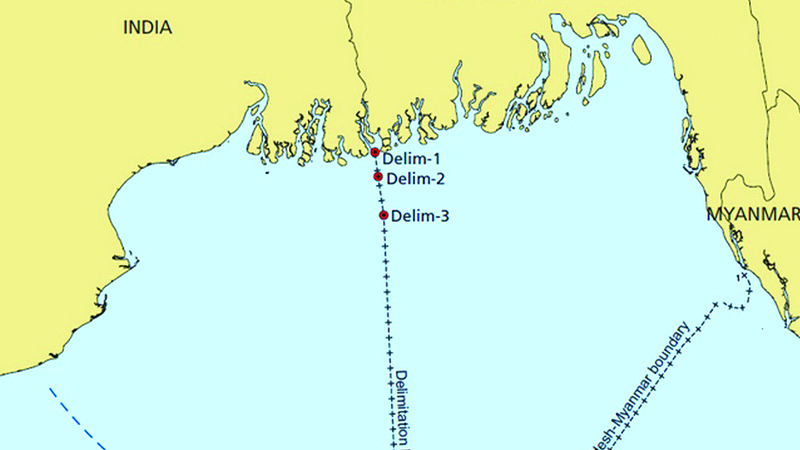

As it has been mentioned previously, a proper definition of what the Blue Economy concept entails is often lacking. According to EU and World Bank definition, the Blue Economy is the range of economic sectors and related policies that together determine whether the use of oceanic resources is sustainable. The Blue Economy concept actually evolved from the concept of an ocean economy. Ocean economy basically points to a specific segment of national economies, and on a broader scale, the global economy itself which is measured by GDP and GVA. Through this came up ways of measuring the part of the economy which is linked to ocean related activities. This was similar to other concepts which also take into consideration segments of the economy in which industries are linked to one another by one or more common features. They are linked in such a way that they function as one whole system instead of separate sectors. Although there are varying definitions of the ocean economy too, the OECD has come up with a definition which defines the ocean economy as the sum of the economic activities of ocean-based industries, and the assets, goods, and services of marine ecosystems (or simply ‘ecosystem assets’). This definition considers four groups of assets: natural capital, produced capital and urban land, human capital and net foreign assets. These four groups together create an ocean economy which consists of many sectors, and each of those sectors in turn are responsible for specific industries or services. Different sources have identified different groups of industries as being parts of these sectors, but a few core groups remain similar. These are: living resources, marine construction, tourism and recreation, boat building and repair, marine transportation, and minerals (oil and gas). This study considered the ocean economy of Bangladesh as the sum of all ocean based economic activities which occur in areas which are under the government’s jurisdiction and the assets, goods, and services which are obtained from the marine ecosystem of Bangladesh.

The study may not have been a complete one, but it was able to provide a baseline measure of the ocean economy of Bangladesh. It constitutes to a little over 3% of the country’s economy in the 2014-2015 fiscal year, and this finding has helped the government set specific targets in relation to the country’s Blue Economy objectives. Some of the reasons why the baselines provided by this study are incomplete are:

1) The output measures exclude some ecosystem services because they are not traded in markets, but that doesn’t mean they are not significant. For e.g.: carbon sequestration and coastal protection services of the mangrove forests of Bangladesh.

2) The measures also do not include the costs which the country has to bear due to the environmental degradation which result from activities in the ocean economy.

Examples include pollution from shipbreaking. Keeping these limitations in mind, there are some obvious benefits in measuring ocean-linked economic activities which take place under Bangladesh’s jurisdiction. The baselines help to identify that these industries and services do not exist in a vacuum, rather they interact with one another by having one common ground, which is the dynamic, three-dimensional ocean. The findings and analyses of this study can make policymakers more aware of the importance of these industries and ecosystem services, which in turn will help them to formulate a more comprehensive approach towards developing them. By raising their awareness, it can help them to lower costs by sharing infrastructure, technologies and infrastructure, reducing the negative effects on the oceans, and in general guide them to use the ocean space more effectively.

Although it would be beneficial for Bangladesh to take a more comprehensive and strategic approach to developing its ocean economy, a policy framework and planning process are still missing. Neither are there any measurable targets, nor suitable monitoring of the process. Currently, it is difficult for Bangladesh to even collect data on its economic output from industries which are included in the definition of ocean economy. Therefore, the most obvious first step is to increase the collection of data from the ocean economy, to better aid with policy making. The next step could be to design various policy scenarios which can be used to develop the country’s ocean economy, using information from the initial assessment of the scope of this section of the country’s economy. Following this, forecasting models can be used to analyse the different scenarios of growth which could take place in Bangladesh’s ocean economy. Through this, policymakers would get an advanced knowledge of the costs and benefits they would be getting if different development pathways for the ocean economy were followed.

Through taking these steps, it is possible for Bangladesh to meet its Blue Economy goals. It is even possible for Bangladesh to become one of the first countries who were able to go from having aspirations to concrete policies and measurable outcomes of progress in their journey of transitioning to a Blue Economy.